Advanced Introduction to Prompt Engineering

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What Is Prompt Engineering (and What It Is Not)

- Why Prompt Engineering Matters Across Disciplines

- A Brief History of Prompting Techniques

4.1. Few-Shot Prompting and In-Context Learning

4.2. Chain-of-Thought and Self-Consistency

4.3. Tools, Agents, and Augmented Prompting - Core Principles of Effective Prompting

5.1. Clarity and Specificity

5.2. Context and Details

5.3. Roles and Personas

5.4. Format and Structure

5.5. Constraints and Guidance

5.6. Tone and Style

5.7. Reasoning and Step-by-Step Thinking - Types of Prompts (Prompting Techniques)

6.1. Zero-Shot Prompting

6.2. One-Shot and Few-Shot Prompting

6.3. Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Prompting

6.4. Self-Consistency and Tree-of-Thoughts

6.5. Other Advanced Prompting Methods - Real-World Examples and Use Cases

7.1. Scientific Research and Data Analysis

7.2. Creative Writing and Content Generation

7.3. Software Development and Coding Assistance

7.4. Education and Training

7.5. Business and Productivity - Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Tips for Improving Prompt Outcomes (Iterative Refinement)

- Reusable Prompt Templates and Cognitive Frameworks

- Prompting Different LLMs

11.1. OpenAI GPT (e.g. GPT-4)

11.2. Anthropic Claude

11.3. Google Models (PaLM, Bard, Gemini)

11.4. Meta LLaMA and Other Open-Source Models

11.5. Mistral, DeepSeek, and Emerging Models - Conclusion and Checklist

1. Introduction

Prompt engineering is the process of crafting and structuring instructions to get the best possible output from a generative AI model. In simple terms, a prompt is the text (or other input) you give to a large language model (LLM) describing the task you want it to do. Prompt engineering, often called an art as much as a science, is essentially the skill of communicating with an AI system effectively. By carefully wording prompts, providing context, and specifying the desired style or format, we can significantly influence an AI’s responses. This discipline has quickly become crucial with the rise of powerful LLMs like GPT-4, Claude, and others, because a well-designed prompt can mean the difference between a useful answer and a misleading mess.

At its core, prompt engineering bridges human creativity and the AI’s technical capabilities. It empowers users (technical and non-technical alike) to guide AI models toward accurate and meaningful outputs. As AI systems spread into fields from education to business, prompt engineering is emerging as a key literacy—one that enables us to “talk” to machines in a way that yields productive results. In this advanced introduction, we’ll define what prompt engineering is (and what it is not), explain why it’s important, and dive deep into the principles and techniques that have evolved to make prompts more effective.

We’ll explore the history of how prompting techniques developed (from early few-shot learning to modern chain-of-thought and tool-using agents), and break down core principles like clarity, context, and providing reasoning steps. We’ll examine different prompt types (zero-shot vs. few-shot, etc.), with real examples across domains—showing how researchers, writers, developers, educators, and business professionals all leverage prompts tailored to their needs. Along the way, we’ll highlight common pitfalls (like ambiguous wording or model “hallucinations”) and how to avoid them, and offer concrete tips for iteratively refining a prompt when the first attempt doesn’t work.

This article is meant to be didactic and accessible: we’ll explain technical concepts clearly (with minimal jargon), provide diagrams and examples to illustrate key ideas, and even include a few interactive practice exercises for you to test your prompt-crafting skills. Finally, we’ll devote a special section to prompting different LLMs, because not all AI models behave the same—what works best for OpenAI’s GPT might differ from prompting Anthropic’s Claude or an open-source model like Meta’s LLaMA. By the end, you should have both a broad understanding of prompt engineering and a set of practical tools and frameworks to craft your own effective prompts.

2. What Is Prompt Engineering (and What It Is Not)

Prompt engineering is fundamentally about writing effective inputs for AI. More formally, it’s “the process of structuring or crafting an instruction in order to produce the best possible output from a generative AI model”. In practice, this means figuring out how to ask a question or give an instruction to an LLM in a way that yields the result you want. A prompt can be as simple as a single question, or a complex directive with context, examples, and constraints. Crafting a good prompt often involves choosing the right wording, providing enough background, and sometimes giving examples or step-by-step guidance so the model understands the task correctly.

It’s also important to clarify what prompt engineering is not. It is not the same as programming in a traditional sense (though it’s sometimes called “AI programming” informally). Unlike writing code in Python or Java, when you engineer a prompt you’re using natural language (or other human-friendly formats) to influence a model’s behavior. You don’t have direct control over the model’s internal logic; instead you guide it. Prompt engineering is also not the same as fine-tuning or training an AI model. Fine-tuning involves adjusting a model’s weights by feeding it lots of labeled examples (a process that leaves a permanent change in the model’s parameters). Prompting, on the other hand, leaves the model unchanged – it’s a zero-shot or few-shot interaction that leverages what the pre-trained model “knows”. As one paper put it, “in prompting, a pre-trained language model is given a prompt (e.g. a natural language instruction) and completes the response without any further training or gradient updates”. In other words, prompt engineering works within the model’s fixed capabilities, coaxing out the desired performance, whereas training or fine-tuning would actually alter those capabilities.

Prompt engineering is sometimes hyped as a magical skill that lets you bend AI to your will, but it has limits. A prompt cannot make an underpowered model suddenly super-intelligent, nor can it force a model to reveal knowledge it simply doesn’t have. What a good prompt can do is tap into the model’s latent knowledge and guide it to present that knowledge usefully. It’s also not a silver bullet: even experts go through trial and error to refine prompts. In fact, prompt crafting is often an iterative process (we’ll discuss techniques for refining prompts in Section 9). Finally, prompt engineering is not a passing fad, at least not at the moment. While some predicted that as models improve, they’d understand plain instructions easily and make prompt engineering less relevant, in reality the opposite has happened: as of 2025 it’s seen as an important skill across industries. The reason is that no matter how advanced the model, how you ask still matters – especially if you want specific, reliable, or creative outcomes.

3. Why Prompt Engineering Matters Across Disciplines

Why all the fuss about prompt engineering? The short answer is that anyone working with AI can benefit from it, whether you’re a scientist analyzing data, a writer drafting content, a developer coding, an educator tutoring, or a business professional generating reports. Large language models are incredibly powerful but also generic; they don’t automatically know exactly what you need. Prompt engineering is the key to customizing an LLM’s output to your context and goals. It’s the interface between human intention and machine generation.

Across disciplines, effective prompting can greatly improve the quality and usefulness of AI outputs. For example, in research, a well-crafted prompt can help an AI summarize a pile of academic papers or even suggest new hypotheses. In education, teachers are learning to design prompts that turn an LLM into a helpful tutor or lesson planner, while students who know how to ask the right questions can get clearer explanations. In writing and media, prompt engineering enables journalists and authors to use AI for brainstorming ideas, drafting articles, or adapting writing to different styles, all while maintaining control over tone and facts. In software development, developers use prompt engineering to interact with code-generation models (like GitHub Copilot or OpenAI’s code models) – the better the prompt (with clear requirements, function signatures, etc.), the more correct the code output tends to be. Businesses are also heavily invested: from marketing copy generation to customer service chatbots, companies find that a small tweak in wording or providing a couple of examples in a prompt can dramatically change the output’s effectiveness for their domain.

It’s worth noting that after ChatGPT’s release in late 2022, prompt engineering quickly became recognized as a valuable skill in the workplace. There are now prompt engineering courses and even job titles for “Prompt Engineer” in some organizations. This reflects a broader point: prompt engineering allows more people (even those without coding expertise) to harness AI tools by speaking their language. Just as the rise of Google made “search engine literacy” important, the rise of LLMs is making prompt literacy important. Those who know how to effectively instruct and query AI can leverage these tools far more efficiently.

Finally, prompt engineering is crucial for responsible AI use. By carefully wording prompts, we can influence models to be more factual and less prone to inappropriate outputs. For instance, a prompt can explicitly instruct the model to base its answer only on provided information (reducing fabrication), or to refuse certain kinds of requests. In disciplines like medicine, law, or finance, where accuracy and compliance are paramount, prompt engineering is part of the process of ensuring the AI’s output meets the necessary standards (we’ll cover pitfalls like hallucinations and how prompting can mitigate them in Section 8). In summary, prompt engineering matters because it unlocks the potential of LLMs across virtually every field – it’s the catalyst that turns a general AI model into a specialized assistant for your particular task.

4. A Brief History of Prompting Techniques

Prompting might seem like a new idea that came with ChatGPT, but its roots go back through years of AI research. Let’s take a quick tour of how prompting techniques evolved, highlighting a few key milestones:

4.1. Few-Shot Prompting and In-Context Learning

One of the earliest breakthrough moments for prompt-based interaction with models came with the advent of few-shot learning in large language models. In 2018, researchers began framing many NLP tasks as question-answer prompts to a single model, hinting that a unified approach was possible. But it was OpenAI’s GPT-3 (2020) that truly popularized in-context learning. The GPT-3 model, with 175 billion parameters, showed a surprising ability: you could give it a task description and a few examples of input-output pairs in the prompt (hence “few-shot”), and it could generalize to produce the correct output for new inputs without any parameter update. The famous paper titled “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners” demonstrated that, for instance, if you wanted GPT-3 to translate a sentence, you could just write:

Translate English to French:

English: I have a pen.

French: J'ai un stylo.

English: How are you?

French:

…and the model would complete the pattern by giving the French translation for “How are you?” in the output. This was remarkable because it treated prompts as training data on the fly – the model was learning the task from the context you provided (the instructions and examples) and doing it immediately. Few-shot prompting showed that, at sufficient scale, LLMs could be prompted to perform many tasks without explicit fine-tuning for each task.

In-context learning via few-shot prompts is considered an emergent capability that only kicks in with large models. Smaller models, when given the same prompt with examples, often don’t improve much. But beyond a certain model size threshold, performance jumps – the model seems to “understand” the prompt format and task. This changed the way AI practitioners approached problems: instead of training a new model for each problem, you could often just prompt a big general model with the right examples. For instance, GPT-3 achieved high accuracies on tasks like reading comprehension, translation, even SAT analogies by using prompt examples, sometimes matching or beating dedicated models for those tasks. This era introduced terms like zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot prompting, referring to how many examples (if any) were included in the prompt. We’ll dig into those prompt types in Section 6. For now, the key point is that few-shot prompting revealed the power of cleverly constructed prompts as a way to get models to do new things without new training.

4.2. Chain-of-Thought and Self-Consistency

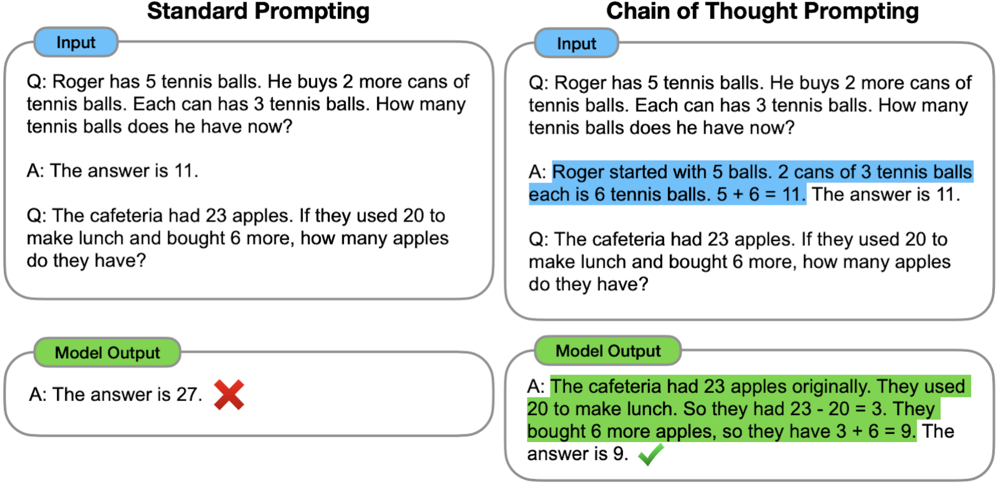

As LLMs continued to grow in capability, researchers noticed that even large models struggled with complex, multi-step reasoning tasks (like multi-step math problems or logic puzzles) when asked to just give a final answer directly. In 2022, a prompting innovation from Google Research called Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting was introduced to address this. The idea of CoT prompting is simple but powerful: instead of prompting the model to jump straight to the answer, you prompt it to think step by step and show its work. Essentially, the prompt is designed to elicit a chain of intermediate reasoning steps that lead to the answer, mimicking how a human might break down a problem.

For example, consider a math word problem:

Q: The cafeteria had 23 apples. If they used 20 to make lunch and then bought 6 more, how many apples do they have?

A standard prompt might just ask the model for the answer (“A: ___?”), which often led to errors. With chain-of-thought prompting, we instead prompt like:

A: Let’s think step by step.

This cue encourages the model to produce a reasoning process: “They had 23 originally, used 20, leaving 3, then bought 6 more, totaling 9. So the answer is 9.” The model then outputs the final answer. Google reported that using CoT prompts with their 540B parameter PaLM model dramatically improved performance on tasks like math word problems – PaLM with CoT reached ~58% on a math benchmark (GSM8K), versus ~18% with a direct prompt. In fact, CoT prompting allowed these large models to match or surpass some task-specific fine-tuned models at the time. The catch was that chain-of-thought prompting only worked well for sufficiently large models (roughly >100B parameters) – another emergent behavior.

Comparison of standard prompting (left) vs. chain-of-thought prompting (right) on math problems. In the CoT approach, the model is induced to break the problem into intermediate steps (highlighted in blue), leading to the correct final answer (green).

Following chain-of-thought’s success, researchers introduced self-consistency decoding in 2023 as an improvement to the technique. Self-consistency involves generating multiple chains of thought (i.e. have the model reason to an answer several times with randomness injected) and then aggregating the results to decide on the most likely correct answer. For instance, you could prompt a model five times with “Let’s think step by step” (using slightly different phrasings or random seeds so it doesn’t produce the same reasoning each time) and end up with five answer candidates. If three out of five chains conclude the answer is “9” and two chains conclude “7”, the final answer would be taken as “9” – basically a majority vote among the model’s own reasoning attempts. This self-consistency approach was shown to significantly boost accuracy on reasoning tasks, as it helps cancel out occasional reasoning glitches by relying on the most common outcome. It’s like getting a second (or fifth) opinion from the model itself and choosing the answer it most consistently arrives at.

Another extension is Tree-of-Thoughts, proposed later in 2023, which generalizes the idea of chain-of-thought into a branching search process. Instead of a single linear chain, the model can explore a reasoning tree – trying different approaches or steps, backtracking if needed, and using techniques like breadth-first or depth-first search to find a solution path. Tree-of-thought prompting treats the model almost like a state-space search algorithm: the prompt or controller encourages exploring multiple possibilities for each step. This method can improve problem-solving on very hard tasks by not putting all eggs in one reasoning basket.

In summary, the 2022–2023 period saw prompting evolve from just “give examples and ask for answer” to “guide the model’s reasoning process explicitly.” Chain-of-thought showed that prompting could unlock reasoning capabilities in LLMs by making them explain to themselves, and follow-up techniques like self-consistency made those explanations more reliable. We’ll cover how to use CoT and related prompts in Section 6.3 and 6.4 for your own tasks.

4.3. Tools, Agents, and Augmented Prompting

The next frontier in prompting has been integrating language models with external tools and turning them into more autonomous agents. Early 2020s research asked: what if we could prompt an LLM not just to answer questions, but to take actions – like doing a web search, using a calculator, or calling an API – and then incorporate the results into its reasoning? This led to prompting frameworks such as ReAct (Reasoning + Acting) and the concept of LLM-based agents.

The ReAct paper (Yao et al., 2022) demonstrated a prompt format that interleaves a model’s thoughts and actions. A ReAct prompt might tell the model it can do certain things (like “Search [query]” or “Lookup [database]”) and encourage it to first output a thought (chain-of-thought style) and then an action, then observe the action’s result, then continue reasoning, and so on. For example, if asked a question about a current event, the model might think “The question is about X, maybe I should search for X” (that’s the reasoning) and then output the special action text “SEARCH X”. The system would execute that (retrieve info) and feed the result back in, and the model continues with another thought, and eventually an answer. With ReAct prompting, the LLM essentially becomes an agent that uses tools in a loop. The ReAct paradigm was important because it combined chain-of-thought with tool use, enabling the model to handle tasks requiring external information or actions beyond pure text generation.

Soon after, we saw the rise of frameworks like LangChain (a popular library for chaining LLM calls and tools) and highly publicized “AI agents” such as Auto-GPT (2023) which attempted to create autonomous GPT-4 agents that recursively prompt themselves to achieve goals. These systems heavily rely on prompt engineering under the hood: they use complex prompt templates that define the agent’s persona, possible actions, and iterative planning behavior. For instance, Auto-GPT would prompt GPT-4 to generate a plan (a series of tasks), then execute tasks one by one, each time re-prompting with results of the previous step – effectively a loop of prompt → action → new prompt. Many of these agentic systems were finicky, often requiring constant prompt tweaking to get useful results. But they showed a direction where prompt engineering blends with program design, giving models “pseudo-embodiment” in an environment.

Another important development is Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), which isn’t exactly a prompt format but a strategy to provide the model with relevant context from outside its training data. In RAG, when the user asks something, the system first does a retrieval (e.g. search a knowledge base or documents) and then constructs a prompt that includes the retrieved snippets along with the user’s query. The prompt might say: “Use the following information to answer the question. Info: [retrieved text]. Question: [user question]?”. This way, the model’s prompt has up-to-date or specialized information it can draw on, reducing the likelihood of hallucinating wrong facts. As Ars Technica described, “RAG is a way of improving LLM performance by blending the LLM process with a web search or other document lookup to help LLMs stick to the facts”. Prompt engineering for RAG involves crafting the right way to insert retrieved facts and perhaps instructions like “if the answer is not in the provided info, say you don’t know” to enforce accuracy. This technique became widely used in enterprise applications to make LLMs useful for tasks like question answering over proprietary data, while keeping outputs grounded in real references. (Section 8 will discuss how such strategies help avoid pitfalls like hallucinations.)

By late 2023 and into 2024, the research community even started automating prompt creation itself (“automatic prompt generation”) and exploring meta-prompting where models critique or refine other models’ outputs (like the Reflexion method or using one model to generate candidate prompts for another). These approaches can be seen as advanced offshoots of prompt engineering, aiming to reduce the manual trial-and-error by letting AI help craft better prompts.

In summary, the historical arc has been: prompts as demonstrations (few-shot) → prompts as reasoning guides (CoT) → prompts as plans/actions (tools & agents). Each step extended what we can do just with clever input phrasing and structure. As we proceed, we’ll cover many of these techniques in detail, and you’ll see echoes of this history in the principles and examples we discuss. Prompt engineering remains a rapidly evolving field – new prompting techniques and best practices are still being discovered as models and use cases expand.

5. Core Principles of Effective Prompting

Having explored what prompt engineering is and how it evolved, let’s distill some core principles for crafting effective prompts. No matter what specific model or task you’re dealing with, these fundamental guidelines will usually apply. Think of them as the ingredients of a good prompt. We’ve broken them down into several categories (clarity, context, etc.), but in practice they often overlap when you write a prompt.

5.1. Clarity and Specificity

Clarity is king in prompt engineering. The instruction you give an AI should be specific, unambiguous, and as detailed as necessary. A common mistake is using language that’s too broad or abstract, which can confuse the model or give it too much room to wander. Instead, clearly state what you want and how you want it. For example, if you need a summary of an article, don’t just say “Summarize this;” say “Summarize the following text in 3 bullet points focusing on the main findings.” Being specific about the desired outcome, length, format, and content helps the model understand the goal. OpenAI’s guidance emphasizes this: “be specific, descriptive and as detailed as possible about the desired context, outcome, length, format, style, etc.”. Vague prompts lead to vague answers, so remove as much ambiguity as you can.

Clarity also means avoiding “fluff” or imprecise wording. Instead of saying “Please make the answer pretty short,” quantify it: “Limit your answer to 2-3 sentences.” In other words, say exactly what you mean. A less effective prompt might ask, “Explain this in simple terms, not too long.” A clearer version would be, “Explain this in simple terms with a single short paragraph (3-5 sentences).” Compare these: “fairly short” vs “3 to 5 sentences” – the latter leaves no doubt about length. Always ask yourself: could this instruction be interpreted in more than one way? If yes, rewrite it to eliminate that ambiguity.

Another facet of clarity is focusing the model on the task and relevant information. If your prompt contains a lot of text (context), you might clarify what to pay attention to. For instance: “Using only the information in the passage below, answer the question…”. This kind of statement steers the model and reduces irrelevant output. It’s often helpful to explicitly mention if you want the model to exclude something (“Do not include any code in the answer” or “Don’t mention X, focus on Y instead”). Interestingly, one nuance is that telling the model what not to do can be less effective than telling it what to do. Instead of a negative instruction alone, it’s better to offer a positive alternative. For example, rather than saying “Don’t make the summary too technical,” you’d say “Provide a summary in plain language, understandable by laypersons (i.e. avoid technical jargon).” This way, you replace the “don’t” with a clear directive of what to do instead, which models handle better.

In short, treat the AI as if it were a very literal-minded person: specify exactly what you want, and if something is crucial, state it plainly. Clarity in prompts yields clarity in outputs.

5.2. Context and Details

Providing context is often critical for getting useful answers. Large language models have no “memory” of your specific situation beyond what you supply in the prompt. So, if you want an accurate, relevant response, feed the model the necessary details up front. Context can include background facts, excerpts from documents, the current date or scenario, or the conversation history in a chat setting. For instance, if you’re asking the model to continue a conversation or answer a question about a text, include the conversation so far or the text passage as part of the prompt (with clear delimitation).

When we say “include context,” we also mean set the stage properly. Imagine you want the model to act as a financial advisor discussing stock portfolios. A contextual prompt might begin: “You are a financial expert with 10 years of experience. The user is seeking advice on balancing a stock portfolio for moderate risk.” Then the user’s query follows. By establishing this context or persona, you guide the model’s perspective and expertise (more on personas in the next section). Context can also be instructions like “Based on the following data: [data], answer the subsequent question.” This ensures the model has the data in the prompt that it should use.

It’s important to remember that models are sensitive to having the right information in the prompt. If something is omitted, the model might fill the gap with a guess (often leading to hallucination). For example, asking “What are the implications of the new policy?” without stating what the policy is will force the model to improvise – not good. Always ask: does the model know what I’m referring to? If not, include that in the prompt explicitly.

However, there is a trade-off: prompts have length limits (a token limit for the model’s context window). So including context means you must select what’s important. Strategies for handling lots of context include summarizing or excerpting only the relevant parts, or using retrieval (as discussed with RAG) to insert just what’s needed. It can also help to tell the model how to use the context: e.g., “Use only the information given below. If details are missing, say you don’t know.” This explicit instruction can prevent the model from going out-of-bounds and making things up.

In essence, the prompt should contain or reference everything the model needs to perform the task. If you want a programming question answered, giving the code snippet in question is context. If you want a letter written about a specific event, describe that event. Think of context as the story or situation you hand to the AI so it has a common ground with you.

Finally, consider ordering and highlighting context. It’s often effective to put the task instruction at the very beginning of the prompt and then include the context, separated by a clear delimiter (like a line of dashes or a token like """). For example:

Summarize the text below into 3 key bullet points.

Text: """

[... long text ...]

"""

This format puts the instruction up front and the material after, which OpenAI notes tends to work well. Using quotes or tags around context helps the model distinguish instruction vs data. The goal is to prevent the model from getting “distracted” or mixing up what it’s supposed to do with the content it’s supposed to act on.

5.3. Roles and Personas

LLMs are very good at role-playing. You can leverage this by assigning the model a role or persona in your prompt. This sets a tone and expectation for how it should respond. For example, starting a prompt with “You are an expert historian of the Roman Empire…” will likely yield a different style and content of answer than “You are a friendly customer service chatbot…”. By defining a role, you constrain the model’s behavior to a certain domain or attitude that’s suitable for your task.

Why use roles? Because models have been trained on internet data filled with conversations and text by various characters and tones. If you say “You are a medical advisor,” the model taps into patterns of medical explanations it learned, adopting a more formal and informative tone. Roles can also implicitly give context – “As a cybersecurity analyst, explain X” clues the model to use security jargon and considerations.

There’s a known prompt format called persona-based prompting where you explicitly set the identity. Some frameworks call it the “Persona” part of a prompt (for instance, an approach called “PARTS” says Persona, Aim, Recipients, Tone, Structure – more on that in Section 10). The persona could be a professional, an emotion (“You are a cheerful assistant”), even a specific famous person’s style (though caution: some models disallow impersonating real people, but stylistic mimicry like “write in the style of Shakespeare” is fine). For non-technical audiences, persona helps clarify the voice: e.g., “Explain like I’m a beginner” vs “Explain as if to a panel of PhD researchers” – the content detail and vocabulary will adjust.

Use case: If a business user wants a marketing email drafted, they might prompt: “You are an experienced marketing copywriter. Write a persuasive email to customers announcing a new product, in a warm and excited tone.” This persona (“experienced marketing copywriter”) guides the style and content to be more on-point than a generic prompt.

One thing to keep in mind is consistency: if you set a role at the start of a chat or prompt, the model will generally stick to it unless redirected. In a multi-turn conversation, it can be useful to occasionally reinforce the persona if the conversation goes long or off-track (like reminding “As a helpful tutor, …”). But usually a strong initial role assignment is enough.

Some advanced usage: You can actually chain personas or combine them. For instance, “You are a debate moderator and an AI ethicist. The user and assistant will debate a topic, and you will ensure the discussion stays factual and respectful.” This would be a complex prompt possibly for multi-agent setups, but it shows you can creatively define roles to shape interactions.

In summary, don’t be shy to tell the model who it is (for this task). It often yields more tailored and context-aware responses. Just remember that the role should suit your needs and be within what the model can do (claiming “You are a sentient AI” won’t actually make it sentient, but it will make it talk as if it were, which might not be useful or truthful).

5.4. Format and Structure

LLMs don’t just spout prose; they can follow quite intricate format instructions if told to. Specifying the structure of the output is a powerful technique. If you need a list, table, JSON, or a particular document layout, say so explicitly in the prompt. For example: “Give the answer as a bullet-point list of 3-5 items.” Or “Respond in JSON format with keys ‘Problem’, ‘Solution’, and ‘Recommendations’.” When you do this, the model will usually comply and produce text in that structure.

This is extremely useful for making the output easier to read or parse by a program. Developers often rely on format instructions so that they can later automatically process the model’s output (e.g., always getting a JSON means you can parse it with code). Keep in mind the model might not always format perfectly – sometimes you have to adjust the prompt or use few-shot examples to reinforce the format.

A handy approach is to provide an example of the format. This is like a mini few-shot demonstration specifically for structure. For instance:

Provide a brief report in the format:

Title: <title here>

Overview: <one sentence overview>

Details:

- Bullet 1

- Bullet 2

Now, generate the report for the following scenario: ...

By showing the template, you reduce ambiguity. The model sees exactly where each piece should go. OpenAI’s best practices call this “Articulate the desired output format through examples – show and tell”. It’s often more effective to demonstrate than to just describe the format.

In some cases, you might not care the exact format but you want a certain logical structure. For instance, “First, provide an introduction, then explain pros and cons in separate paragraphs, and conclude with a recommendation.” This kind of guiding outline can be given as part of the prompt. The model will then attempt to produce text following that outline.

Remember, the model is a pattern learner – if your prompt sets up a pattern, it will try to continue it. If you want a Q\&A format, you can literally prompt with “Q: [question]\nA:” and often it will continue with the answer. This continuation ability is a simple but effective formatting trick.

One word of caution: sometimes if you over-constrain the format, the model might say something like “I can’t do that” or it might break the format if the content is too complex. It can take a bit of experimentation to get the prompt right so that the structure is obeyed without losing content quality. If the model ignores the format instructions, you likely need to either make those instructions more prominent (earlier in prompt, or separated clearly) or give a direct example as mentioned.

In summary, think about what shape you want the answer in, and encode that in the prompt. Models will happily output lists, sections, code blocks, or any structure you define – they just need to know the rules up front.

5.5. Constraints and Guidance

Beyond format, you can set various constraints on the output or guide the content in subtle ways. Constraints include things like word limit, style guidelines, or content boundaries. We touched on length (e.g., “answer in 100 words or fewer”) which is one common constraint. But you can also instruct the model on the level of detail (“include at least one quantitative example”), the focus (“emphasize the health benefits, and mention no more than a passing reference to cost”), or style (“write in a casual tone, using analogies to explain concepts”).

Guidance often involves telling the model how to approach the task. For example, if you have a complex problem, you might explicitly say “Solve this step by step. First outline a plan, then proceed with each step.” This mixes constraint (the process it should follow) with guidance (reminding it to break down the problem). Another example: “If you don’t know the exact answer, make a reasonable assumption and state that you assumed it.” You’re giving the model instructions on what to do in an uncertain situation, which can lead to more sensible outputs instead of pure hallucination.

A valuable constraint in some contexts is instructing the model about what not to do, but remember the earlier advice: pair “don’t do X” with a suggestion of what to do instead. For instance, “Do not copy any text verbatim from the source; instead, paraphrase the content in your own words.” This not only forbids an action (copying) but provides a guided alternative (paraphrasing). In customer support scenarios, you might say “Do not ask the user for their password; if account-specific info is needed, guide them to the account recovery page instead”. This way the model has a clear path to follow that avoids a disallowed behavior.

Constraints can also involve tone and politeness levels if that’s important. For example, “Respond politely and helpfully, avoiding any slang or overly casual language.” This ensures the assistant doesn’t, say, joke around if that’s not appropriate.

In specialized tasks like coding, constraints might be technical: “The SQL query should not use subqueries” or “The Python code must run in O(n) time complexity.” Amazingly, models often attempt to respect even complex constraints like these if they understand them, though the success may vary with the model’s expertise.

When giving constraints, put them near the beginning of the prompt if they’re critical. You can even bullet them in the prompt for clarity, like:

When writing the answer, follow these rules:

- Limit the answer to one paragraph.

- Use a neutral, factual tone.

- Do not reveal any internal variables or code (if any).

This explicitly enumerated list of dos/don’ts can be very effective.

Finally, be aware that some models have system-level constraints that you can’t override by prompting (like refusal to produce disallowed content due to safety layers). Prompt engineering within ethical bounds is fine, but attempting to get the model to break its fundamental rules (e.g., prompt-injection to get around content filters) is not recommended and often won’t succeed in latest models. It’s better to work with the model’s guidelines: if it refuses because it was too sensitive a request, rephrase to a safer or more abstract version. We’ll discuss prompt injection and related pitfalls in Section 8.

5.6. Tone and Style

The tone of a response can be just as important as the factual content, especially if the output is user-facing. Luckily, tone and style are something you can strongly influence via the prompt. If you want a formal tone: say so. If you want it funny: explicitly request humor or a casual style. Models are good at mimicking styles from “Shakespearean sonnet” to “social media tweet-speak” as long as you clearly indicate it.

Some techniques for tone control include:

- Using adjectives in the instruction: “Provide a friendly and optimistic explanation of…” or “Give a concise, professional summary of…”. Adjectives like friendly, formal, academic, witty, somber, etc. set the mood.

- Specifying audience or medium: “Explain in a manner suitable for a children’s book” will invoke simpler vocabulary and a gentle tone. Or “Write as a blog post on a tech website” might yield an informative yet conversational tone. By indicating the target audience (“for laypersons”, “for domain experts”) or format (“like a news article”, “like a speech”), you indirectly set style expectations.

- Providing style examples: In few-shot examples, the way your example answers are written will be mirrored. If you provide one sample answer that’s very formal, the model will likely follow that style for the next answer.

- Using literary or famous references: “Respond in the style of Sherlock Holmes narrations” or “Answer as if Yoda from Star Wars were speaking.” These can be fun and surprisingly accurate. (Note: ensure such stylistic mimicry is allowable by the platform; it usually is for public figures or fictional characters in terms of style, but not for private individuals.)

Be mindful of consistency: if you want a certain tone, apply it throughout the prompt. Your own user query part could even be phrased in a way that sets tone context (e.g., if you write in old English, the model might mirror it).

One interesting aspect is politeness. If you are using a model in an interactive setting, you might instruct it on being polite or empathic. For instance, customer service bots often have a system prompt like: “You are a customer service assistant: helpful, empathetic, and concise.” Including words like empathetic or apologetic where needed ensures the model’s style includes those elements (e.g. “I’m sorry to hear that you’re facing this issue…”).

Tone also ties to the earlier persona point: the persona often implies a tone. “You are a witty comedian” vs “You are a strict grammar teacher” – one will naturally respond with humor, the other with precision and possibly pedantic language.

In summary, don’t leave tone to chance. If the scenario calls for a particular voice, make it part of the prompt. The AI doesn’t have an inherent personality (besides some defaults from training like being generally polite by default), so it will adopt whatever persona or style you command, within reason. This is a powerful way to ensure the output fits the context (professional for a business report, casual for a friendly advice, etc.).

5.7. Reasoning and Step-by-Step Thinking

One of the most impactful prompt principles is to explicitly encourage the model to show its reasoning or proceed step by step. As we discussed with chain-of-thought prompting, sometimes telling the model “Let’s think step by step” or asking for an explanation can dramatically improve the quality of the answer for complex problems. The model essentially uses more of its “brain power” to reason through the problem instead of guessing the answer outright.

However, there are different ways to apply this principle:

- Ask for rationale: e.g., “Explain your reasoning before giving the final answer” or “Show the calculations and logic you use to arrive at the conclusion.” This often yields a multi-part answer where the first part is reasoning and the last part is the answer. Not only does this help you verify the answer, but the process of reasoning can lead to more correct answers in the first place.

- Step-by-step directive: You can break the prompt into steps explicitly. “Step 1: Summarize the problem. Step 2: List possible approaches. Step 3: Work out the solution. Step 4: Provide the final answer.” The model will then fill in those steps. This is a very controlled way of getting reasoning, essentially dividing the task. You might even number your expected answer parts (“1)… 2)…”) and the model will follow that outline.

- Chain-of-thought in hidden mode: Some users do a prompt trick where they ask the model to produce reasoning but then only output the answer (like “Think through the solution step by step internally, then just give the final answer”). The effectiveness of this varies by model – some might actually show the reasoning anyway or not follow it. But the idea is to get the benefit of reasoning without the clutter in the final output if you don’t want it. With certain API settings, one can capture the reasoning separately (for instance, by instructing the model that anything in parentheses is its scratchpad).

- Use reasoning words or format: Simply including phrases like “Let’s think this through:” or starting an answer with “First,… then,… finally,…” in your prompt examples can gear the model into a logical mode. If you see the model giving superficial answers, it might be because the question was asked in a way that didn’t hint that deeper reasoning was needed.

There is a balance: for straightforward tasks (like a simple fact lookup), forcing a step-by-step might be overkill and could even lead to the model fabricating steps. But for math problems, logic puzzles, complex decision-making or when you specifically want an explanation, it’s highly useful.

Another advanced reasoning prompt technique is self-critique or checking. For instance, after an answer, you could prompt the model to review it: “Now double-check the answer above. Is there any flaw in the reasoning? If so, correct it.” This turns the model into its own reviewer. Anthropic’s Claude model, for example, was trained with a technique (“Constitutional AI”) where it internally does something similar – reflecting on whether the answer follows certain principles. You can manually invoke this behavior with a two-step approach: get an initial answer, then feed it back with “Critique this” prompt, then refine. While this is not one single prompt, it’s part of prompt engineering in a multi-turn sense.

One must also mention: if you use chain-of-thought prompting in a setting where the user sees the output (like ChatGPT interface), the reasoning will be visible to them. In some cases that’s fine (they want to see it), but in others you might only want the final answer visible. In a deployed solution, you might capture the reasoning and strip it out before showing the user. But as a human prompter using ChatGPT, seeing the reasoning might actually help you trust or debug the answer.

Finally, a bit of math: sometimes we explicitly need the model to follow a formula or do a calculation. You might include a formula in the prompt or encourage a certain approach (“Use the formula distance = rate * time to solve this problem”). Models can do arithmetic to a degree, but they are not guaranteed calculators. So if high precision is needed, one might use a tool (like call an actual calculator via a tool-use prompt). But for moderate calculations, showing each step can prevent the model from making arithmetic mistakes or at least let you catch them.

In conclusion, think about whether your task would benefit from the model reasoning out loud. If yes, nudge it to do so in the prompt. It often leads to better results and more transparency. As the saying goes in AI circles: “Let’s think step by step” has become almost a magical phrase for unlocking an LLM’s reasoning power.

6. Types of Prompts (Prompting Techniques)

Prompt engineering isn’t one-size-fits-all. Depending on what you’re trying to accomplish, you might use different prompting techniques. Here we’ll outline several common types of prompts and when to use them: zero-shot, one-shot, few-shot, chain-of-thought, self-consistency (and tree-of-thought), and some other advanced patterns. We’ve touched on many of these in the historical overview, but now we’ll describe them from a practical usage perspective.

6.1. Zero-Shot Prompting

Zero-shot prompting means you ask the model to do a task without giving any examples. It’s just your instruction and perhaps some context, and then the model must respond from its general knowledge. For example: “Translate the following sentence to Spanish: [sentence here].” This is zero-shot because you didn’t show any example translations; you assume the model knows how to translate in general (which large models often do, thanks to training data).

Zero-shot is the simplest and often the first thing you try. Modern large models (like GPT-4 or Claude) are remarkably capable zero-shot. They’ve effectively “learned” many tasks during training just by reading so much internet text. So, if your task is straightforward or very common (summarization, translation, Q\&A, etc.), a zero-shot prompt might be all you need. It’s efficient because you’re not wasting prompt space on examples.

However, zero-shot might not always yield the best result. Without examples, the model might be unsure what style or format you want, or it might fall back on a generic response style. That’s where the other techniques come in. But always remember: if you can clearly describe the task in words, you often don’t need examples. For instance, “List 5 key points about the water cycle” is likely to get a decent answer zero-shot.

One place zero-shot can struggle is when the task is unusual or very specific in format. The model might not know from just the instruction exactly how to structure the output. For example, “Create a to-do list for moving to a new house” – the model will do it zero-shot, but if you wanted those to-dos in a particular style, you may need to either specify that or give an example.

In summary, zero-shot = instruction-only. Use it when:

- The task is simple or standard.

- The model is powerful or fine-tuned for instructions (most big models in 2025 are).

- You don’t have good example data or want to save tokens.

It’s often a good starting point: “Try zero-shot, if output is not satisfactory, then escalate to few-shot.”

Exercise (Try Zero-Shot): Without providing any examples, prompt the AI to “Write a two-sentence biography of Ada Lovelace in a friendly tone.” See what it comes up with. Does it meet the criteria? This tests how well the model does with clear instructions alone. If the result isn’t as friendly or exactly two sentences, you might refine the instruction, but likely it’ll be fine.

6.2. One-Shot and Few-Shot Prompting

One-shot prompting provides exactly one example of the task in the prompt. Few-shot provides a few (more than one, usually 2-5) examples. The idea, as discussed earlier, is to show the model how it should perform the task by demonstration, rather than just telling it.

When to use one-shot or few-shot:

- The task might be understood by the model, but you want to set a particular style or format via example.

- The task is niche or complex, and you suspect the model would do better seeing at least one example.

- The instructions alone aren’t yielding what you want, and an example can anchor the model’s output.

One-shot example: Suppose you want the model to convert movie titles into emojis for fun. You prompt:

Convert movie titles into string of relevant emojis.

Example:

Movie: The Lion King

Emojis: 🦁👑🐗🐆

Movie: Titanic

Emojis:

Here, we gave one example (“The Lion King” -> some emojis). Now the model is likely to mimic that for “Titanic” when completing. Without the example, it might do something else or not know exactly the format you expect (maybe it’d give “Ship, iceberg, heart” etc., but example ensures it uses the same approach and formatting like “Movie: X\nEmojis: …”).

Few-shot example: You’re creating a mini FAQ bot with Q\&A. You might prompt:

Q: What is the capital of France?

A: Paris.

Q: Who wrote the novel "1984"?

A: George Orwell.

Q: What is the square root of 144?

A:

By providing two QA pairs, you both supply facts (if needed, though the model knows these likely) and crucially, you set the formatting of Q: and A:. The model will continue with A: 12. for the last question because it sees the pattern.

Few-shot shines for tasks like classification or transformation where examples really clarify the task. For instance, sentiment analysis:

Text: "I absolutely loved the new restaurant!" -> Sentiment: Positive

Text: "The movie was okay, nothing special." -> Sentiment: Neutral

Text: "This product is terrible and broke on day one." -> Sentiment: Negative

Text: "I'm not sure how I feel about this." -> Sentiment:

The examples basically train the model in context to do sentiment analysis with that format.

Why not always use few-shot? Because it takes more prompt space (which is limited) and sometimes it’s unnecessary. If the model already knows how to do something, examples might not improve things and could even confuse if not well-chosen. Also, if your examples are poor or not representative, they can mislead the model.

There’s also a subtle art to picking examples if you do few-shot:

- They should be relevant to the range of inputs you expect (cover different cases if possible).

- They should be correct (obviously, you don’t want to teach the model wrong).

- They ideally should be diverse enough to convey the pattern, but not so diverse that they confuse the pattern.

One approach is to start with zero-shot, observe model errors, then incorporate a few examples addressing those errors. This is like model-assisted prompt development.

One-shot vs Few-shot: One-shot might be enough if the model just needed a slight nudge or format example. Few-shot is better when more context helps disambiguate. But more than maybe 5-6 examples rarely helps significantly due to diminishing returns (and you might run out of space).

It’s worth noting: few-shot prompts are performing a kind of in-context learning – the model is effectively learning from those examples each time it answers. Large models have shown they can generalize from surprisingly few examples to something slightly new (like in one example you never showed a particular category, but they infer how to handle it if similar).

Exercise (Design Few-Shot): Say you want the model to generate analogies for technology concepts. Craft a few-shot prompt with 2 examples. For instance:

Concept: The Internet

Analogy: The internet is like a vast library where each book is a website and librarians help you find information instantly.

Concept: DNA

Analogy: DNA is like a recipe book for life, with genes as the individual recipes that tell cells how to behave.

Concept: **Artificial Intelligence**

Analogy:

Try completing this. The examples guide the structure (concept -> analogy with a certain phrasing style). Does the new analogy follow suit?

6.3. Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Prompting

As covered earlier, Chain-of-Thought prompting is when you prompt the model to generate a step-by-step reasoning path before giving the final answer. In practice, using CoT often means appending something like “Let’s think step by step” to your question, or explicitly asking for an explanation. CoT can be combined with zero-shot or few-shot. In the original Google paper, they used few-shot with CoT examples (to really nudge the model into that format), but it’s been found that with newer models you can often just do zero-shot CoT by instructing the reasoning.

When to use CoT: When the problem involves arithmetic, logical reasoning, multi-hop inference, or anything where a structured reasoning process is needed. Math word problems are a classic case. Another is tricky common-sense questions or puzzles. For example: Q: “Alice has 5 apples, Bob has twice as many as Alice, and Charlie has 3 less than Bob. How many apples do they have in total?” If you ask directly, the model might get it right or not. But if you say, “Solve step by step:” it’ll do the intermediate math (Alice 5; Bob 10; Charlie 7; total 22) and likely get it right.

How to implement CoT in your prompt:

- Easiest: just tell the model to think aloud. e.g., “Show your reasoning step by step, then give the answer.”

- Or include a few-shot example of a Q-> stepwise reasoning -> A.

- If you’re using an interactive setting like ChatGPT, you can ask in one turn “Can you explain your reasoning?” and in next, refine. But often one prompt is enough: e.g. “Explain the reasoning and then answer.”

Quality of reasoning: Keep in mind the model’s reasoning isn’t guaranteed to be logically perfect. It can make mistakes in the chain-of-thought too. But generally, if the final answer is correct, the reasoning will be consistent. If the reasoning has an error, sometimes the final answer might still be right by coincidence, or vice versa. Use CoT as a tool to diagnose or improve accuracy, but always double-check if it’s a critical task.

In non-math scenarios, chain-of-thought can help with things like planning tasks or writing outlines. For instance, prompting “First, outline the structure of the essay. Then write the essay following that outline.” This is a kind of CoT for writing – first the plan (steps), then the outcome.

Multi-step instructions vs CoT: They overlap. If you give an instruction broken into parts, that’s like forcing a chain-of-thought structure. CoT in free form (just “think aloud”) lets the model decide the steps. Both can work; the former gives you more control, the latter might reveal interesting reasoning.

A quick example: Prompt: “What is the cheapest way to travel from New York to Boston? Let’s think step by step.” The model might enumerate: “Step 1: Consider travel options (car, bus, train, flight). Step 2: Research typical prices… Step 3: Compare and conclude bus is cheapest. Answer: likely taking a bus is cheapest.” Without that, it might just say “Probably the bus.” But the chain gives a fuller answer.

One caution: if you don’t actually want the user to see the reasoning, you’ll have to strip it out or instruct the model not to show it. But often, showing the reasoning is a feature, not a bug, for explainability.

6.4. Self-Consistency and Tree-of-Thoughts

These are more advanced prompting techniques that build on chain-of-thought. They often require orchestrating multiple prompts or generations, but conceptually it’s part of prompt engineering to set them up.

Self-Consistency (CoT voting): The prompt itself for one run might not differ – it’s more about doing multiple runs with randomness. But you might implement it by adding a small instruction like “Think of a solution, and you can approach it in different ways if needed.” Honestly, the model doesn’t have a built-in “sample multiple times” ability in one prompt – you as the user do that. So self-consistency is less about prompt content and more about calling the model several times with the same CoT prompt and a temperature > 0 to get varied reasoning. After that, you choose the answer that appears most often. In an interactive use, you could do this manually (“Give three different solutions to this problem, then tell me which answer appears most frequently among them.”). In fact, that’s one way to prompt it – ask the model itself to generate multiple answers and then pick: e.g., “Try solving this problem 3 independent times and list your 3 answers. Then conclude which answer is the most common or likely correct.” That’s a single prompt trick to emulate self-consistency. The model might literally print three attempts and then the choice.

Tree-of-Thoughts: This is harder to implement with plain prompting, because it implies branching. However, you can prompt a model to simulate a tree search. One way:

- The model could be instructed: “Consider multiple possible reasoning paths. Explore option A: … (if it leads to dead end, backtrack), then option B: … Finally give the best solution found.” This is quite complex and might not reliably cause actual backtracking or breadth search unless coupled with an algorithm external to the model. In practice, tree-of-thought is more of a methodology where you as the controller feed partial thoughts and see outcomes. For example, you prompt for possible next steps, then evaluate with the model, etc.

Because tree-of-thought prompting is an active research idea, there’s no standard one-prompt recipe for users like chain-of-thought is. If you’re coding, you might do:

- Prompt model to list possible first steps.

- For each, prompt model to continue the reasoning.

- Evaluate outcomes somehow (maybe ask the model to give a score or check if solved).

- Choose next branch to expand. That requires multiple prompt calls.

For the scope of this article, just know it exists: It’s basically multiple chains of thought in a search paradigm. If you ever see a need where the model should consider alternatives, you can manually prompt something like, “List two different approaches to solve this problem, then examine each and tell me which yields a better result.” That captures the spirit (two branches, then selection).

In summary for self-consistency & tree-of-thoughts: These aren’t typically single-shot prompt phrasings you can casually throw in (aside from asking for multiple answers). They are techniques at the session or script level. They illustrate that sometimes one answer from the model isn’t enough – you either want consensus from many answers (self-consistency) or to explore many answer paths (tree search). When extremely high reliability is needed, these can be useful. But for everyday use, usually either a good CoT or a well-chosen prompt suffices.

6.5. Other Advanced Prompting Methods

We’ve covered the big ones, but let’s briefly note a few other prompt techniques and patterns that can be useful:

-

Instruction with reflection (Reflexion): This approach has the model generate an initial answer, then critique its own answer, then improve it. You can prompt this explicitly in one go: “Answer the question, then review your answer for any errors or omissions, and finally provide a corrected final answer.” This way, the model basically does a two-pass on the response within one prompt. It might output something like: “Draft answer: … [some answer]. Review: I realize I forgot to consider Y, and I made a mistake in calculation. Final Answer: … [corrected answer].” This is advanced in that not all models reliably do it, but it’s a clever use of prompting for quality control.

-

Role-playing multi-turn: Sometimes you achieve things by prompting in multiple turns. For example, you can first prompt “You are a problem solver. I will give you a problem, you break it into steps first.” Then you give the problem, it breaks into steps. Then you prompt step by step. This is more of a strategy than a single prompt technique, but it’s relevant to prompt engineering in that you design a sequence of prompts. This can be needed if a task is too complex to solve in one shot; you essentially guide the model through it (like you would an employee: first do analysis, then do execution).

-

Meta-prompts (asking the model to create prompts): You can ask a model to generate a good prompt for another model or for itself given a goal. For instance, “What should I ask you to get a detailed explanation of quantum physics?” and then use that. This is more exploratory, but it can yield insight into how the model interprets tasks.

-

Few-shot with negative examples: Sometimes called “contrastive prompting”. You show one bad attempt and a correction. E.g., “Question: …; Bad answer: … (this answer is incorrect because…). Good answer: …” This can steer the model away from certain mistakes or styles by explicitly showing what not to do. It’s not commonly needed, but it’s possible.

-

Visual or multi-modal prompting: If the model can accept images (like some can, e.g., GPT-4 with vision or Google Gemini if multi-modal), prompting includes describing or pointing to images. For example, “Here is an image [image]. Describe it in a humorous way.” The principles remain similar (clarity, context, etc.), but you have an extra modality. This is cutting-edge and specific to certain models.

-

Tool use directives: With models that support tools or APIs (e.g., function calling in OpenAI or plug-ins, or agent frameworks), you might include special tokens or formats in the prompt to invoke those. For instance, with OpenAI’s function calling, the system message might include a function schema, and your user prompt might naturally lead to a function call. This is an advanced integration but basically you prompt the model in a way that it knows using a function/tool is appropriate (“search for X” in the reasoning, etc., as ReAct does).

The landscape of prompting techniques is always expanding. But the ones we described in detail (zero, few, CoT, etc.) are the bread-and-butter that cover the majority of use cases.

To close this section, remember that prompt engineering is often about combining techniques. You might do few-shot + CoT at the same time (example with reasoning shown). Or role + zero-shot, etc. The ultimate prompt might incorporate many of the principles and techniques: e.g.,

“You are a financial advisor. The user will provide a short description of their financial situation. Provide a step-by-step analysis of their situation, then a final recommendation at the end. Use a polite and reassuring tone. If information is missing, note the assumption you make. Answer in at most 4 paragraphs.”

The above prompt (perhaps followed by the user’s info) combines context (role), reasoning steps, tone, assumptions guidance, and length constraint all in one. And that’s a perfectly fine way to do it – you don’t need to compartmentalize each technique as long as the prompt remains coherent and not contradictory.

7. Real-World Examples and Use Cases

Let’s move from theory to practice. How is prompt engineering actually applied in the real world? In virtually every field where LLMs or generative AI are being used, prompt crafting plays a role in getting useful results. We’ll go through a few domains and illustrate with examples how prompts are used, along with any special considerations in each area.

7.1. Scientific Research and Data Analysis

Research: Academics and scientists use LLMs to help summarize literature, generate hypotheses, explain complex concepts, or even brainstorm experimental designs. For example, a researcher might prompt an AI: “Summarize the key findings of these three papers on quantum thermodynamics and highlight any conflicting results.” To do this effectively, the prompt likely includes either the paper abstracts or key points (context), and instructions to compare them. The prompt might need to emphasize accuracy and not fabricating data (a common pitfall in research settings). So a good prompt could be: “Using the provided abstracts, compare the key findings. If details are not available in the text, say that explicitly rather than guessing.” This ensures the model doesn’t hallucinate a result. Researchers also might use CoT prompting to have the model reason through a scientific question (e.g., analyzing how changing one variable might impact an experiment, step by step). When writing academic text, they may instruct the model to use a formal tone and even include citations if the model can do that (some models are trained to output references).

A concrete use case: Literature review assistance. A researcher provides a list of bullet points from papers and prompts the model: “Draft a literature review from the following points, grouping them by theme. Use an academic tone and do not include any information not given.” The model then produces a draft which the researcher can verify and edit. Prompting here needed to emphasize using only given info to avoid made-up content, which is crucial in scientific integrity.

Data Analysis: While LLMs aren’t spreadsheet calculators, they can assist in explaining data or suggesting interpretations. For instance, if you have some statistical results and you paste them in, you could prompt: “Explain in plain English what the following statistical results mean and any caveats: [insert results].” Because the model isn’t a domain expert necessarily, providing context like what the data is about will help. Analysts also use prompts to generate code for data analysis (like writing a Python script for a certain analysis). For example: “You are a Python data analyst. Write code to load a CSV, compute summary statistics (mean, median, std) for each column, and output the results.” The model then produces code – essentially acting like Copilot.

In scientific computing or math, one might prompt CoT for solving a problem or deriving a formula. E.g., “Derive the formula for the area of a circle using calculus, step by step.” The chain-of-thought here ensures the derivation steps are shown. For verification, one could further ask the model to plug in specific values to test the formula, etc.

A key point in research use cases is verification. Prompts often need to encourage the model to provide sources or to express uncertainty when unsure, because a confident-sounding but wrong answer can be dangerous in research. A prompt might explicitly say: “If you are not sure about a fact or it’s not in the given data, state that you are unsure.” This guides the model to be cautious.

7.2. Creative Writing and Content Generation

LLMs are widely used for generating creative content: stories, blog posts, marketing copy, poetry, you name it. Here prompt engineering is about coaxing a certain style or creative angle.

Creative writing (stories, poems): Prompts might set a scene or style. For example: “Write a short story (150-200 words) in the style of a noir detective novel, where the main character is a cat investigating a missing toy.” This prompt includes length guidance, genre/tone, and a quirky twist. The model will likely produce a fun little story hitting those notes. If the first try isn’t noir enough, you could refine the prompt to emphasize mood: “Focus on creating a suspenseful, moody atmosphere, with first-person narration full of witty internal monologue.” See how adding detail in the prompt changes the output tone dramatically.

For poetry, you might specify form or rhyme scheme: “Write a sonnet (14 lines of iambic pentameter) about the passing of seasons.” The model can indeed attempt a sonnet structure. Or a haiku: “Compose a haiku about the feeling of sunlight after rain.” These clearly defined structures often yield better results when named.

Marketing and business content: Suppose you need an email to customers or a product description. A prompt could be: “You are a marketing copywriter. Write a promotional email for [Product], highlighting [key features], in a enthusiastic and clear tone, about 3 short paragraphs long. Include a catchy subject line as well.” This prompt covers role, task, style, length, and even a specific output element (subject line). The model might produce a decent draft that you can then tweak for accuracy or branding.

One challenge in creative generation is avoiding cliches or repetitive phrasing. If you notice the model always starts e.g. blog posts with “In today’s world, …”, you can explicitly forbid that or give an example of a different opening. For instance: “Start with an engaging hook – e.g., a question or surprising fact – rather than a generic statement.” That level of instruction can push the model to be more original. But of course, the model has its patterns; sometimes multiple attempts or later human editing is needed to really polish creative work.

Use Case – Blogging: Let’s say you want to write a tutorial article. You might prompt: “Draft a blog article titled ‘Getting Started with Prompt Engineering’. The audience is non-technical, so use simple language. Include an introduction, 3 main sections with headings, and a conclusion. Provide a couple of examples in the middle as illustration (maybe a sample prompt and its output). End with an encouraging call-to-action for readers to try prompt engineering.” This rather detailed prompt effectively gives the model a blueprint. The output might be a fairly well-structured draft blog. Your job then is more to correct any factual inaccuracies and add personal touches rather than writing from scratch.

Interactive Fiction or Dialogues: If using the model to simulate characters (like a game or training scenario), prompt engineering might involve giving the model background on the characters and instructions to stay in character. For example: System prompt: “You are the narrator in a fantasy interactive fiction. The user plays a hero. Always respond as the world and characters around the hero, describing scenes vividly and asking the user what they do next. Do not reveal game mechanics.” User prompt: “Start the adventure, the hero enters a dark forest.” This kind of prompting sets up an entire interactive style. It’s more complex, but it shows how important the prompt (especially the initial system prompt or persona) is for long-form creative tasks.

7.3. Software Development and Coding Assistance

Software developers use LLMs as coding copilots – to generate code, explain code, or help debug. Prompt engineering for coding is a bit of an art on its own, since here the format and correctness are crucial.

Code generation: A typical prompt might be: “Write a Python function that takes a list of integers and returns the list sorted in ascending order using the bubble sort algorithm. Include comments explaining each step.” This prompt clearly states language (Python), what the function does, and even which algorithm to use (bubble sort) plus a style requirement (comments). The model should output valid Python code. Developers often include the function signature if they want it certain: e.g., start with def bubble_sort(arr): in the prompt to ensure the model continues under that function. If there’s a specific library to use or avoid, that can be stated (“without using built-in sort functions”).

A great practice in code prompting is giving examples of input/output if possible. For instance: “Function should do X. Example: if input is [5, 2, 9], the function returns [2, 5, 9].” By providing that, you both clarify the requirement and allow the model to possibly include a test in a docstring or at least double-check logic internally.

Also, as seen in earlier sections, using leading triggers can help code output. OpenAI noted putting import as a starting word in a code prompt nudges the model to produce code (since code often starts with imports). For SQL, starting with SELECT might prompt an actual SQL query output.

Code explanation: Sometimes you have code and want an explanation. You can prompt: “Here’s some code: <code> Explain what this code does in simple terms.” The model will describe it. If you want a certain format (like bullet points vs paragraph), specify that. Or “Identify any potential bugs or inefficiencies in the code and suggest improvements.” The model can perform a code review style output.

Debugging: You can copy an error message and code into a prompt. For example: “This Python code is supposed to do X, but it’s throwing an error. Code:\n<code here>\nError:\n\n<error traceback>\n\nWhat is causing the error and how can I fix it?” The model will try to analyze the traceback and code logic to provide a solution. This is hugely helpful for developers, though you must verify the correctness of the advice (models sometimes hallucinate non-existent functions or misread code).

Completion context: In an IDE integration, the “prompt” might be the file content and your comment as instruction. But in conversational use, you just paste the relevant stuff.

Caveat: Models can produce syntactically correct code that doesn’t actually solve the problem at hand or has subtle bugs. So often the prompt needs to pin down specifics (“must handle edge case of empty input”, etc.). And even then, testing the code is needed. Prompt engineering in coding sometimes involves iterative refinement: run the model’s code, see if tests fail, if so, tell the model the failing scenario, get a fix.

Use Case – Documentation generation: A developer might prompt: “Generate documentation comments for the following function.” and provide the function code. The model then creates a docstring or comments explaining parameters and returns. This can speed up writing docs.

An advanced scenario: Using tools within code – e.g., the model knows about certain API calls. Some specialized coding models allow calling documentation or running code. But even without that, you could prompt: “If needed, refer to Python’s official documentation for json library to ensure correct usage.” The model doesn’t truly go read docs unless it was trained on them, but it might recall them.

Also note, many models have a limit on how many characters they’ll output in one go. For very long code, you might have to prompt piecewise or ask for just the important parts, etc. If the model stops midway (common for longer outputs), you can usually just say “continue from where you left off” and it will resume (as the context still has the prompt and partial answer).

7.4. Education and Training

Education: Teachers and students use prompt engineering to extract educational value from LLMs. For instance, a student might prompt an explanation: “Explain the concept of supply and demand in economics using a simple analogy, as if I’m 12 years old.” That’s a straightforward educational query, using role/tone (“as if I’m 12”) to adjust complexity. If the explanation comes and the student still doesn’t get it, they could refine: “Thanks. Can you give a numerical example of supply and demand with actual numbers and outcomes?” Prompt engineering here is about scaffolding learning – breaking down a concept into digestible pieces via follow-up prompts.

Teachers might use prompts to generate quiz questions: “Generate 5 multiple-choice questions (with answers) to test understanding of the Pythagorean theorem.” The prompt would perhaps specify difficulty or format too. The model then outputs Q\&A pairs. It’s wise to review them for correctness (sometimes it might ask a weird or incorrect question), but it’s a time-saver for educators.

Another use is lesson plans: “Create a lesson plan for a 1-hour class on the water cycle for 8th grade science. Include an introduction, a hands-on activity, and a conclusion.” The prompt clearly sets the stage (audience 8th grade, subject water cycle, structure required). The model could outline a decent lesson structure. The teacher can then adapt it.

Tutoring via prompts: Some people use LLMs as a personal tutor. For example: “I’m going to practice French. Please act as a French tutor. Speak to me only in French and correct my sentences if I make mistakes, providing the corrections in English.” This prompt defines a role and instructions on corrections. Then the user might write a French sentence, the model responds (in French) plus any corrections. It’s a dynamic use of prompt where the initial user message set the stage for an ongoing behavior.

Another example, for coding education: “Pretend I don’t know what a for-loop is. Teach me from basics, then give me a simple exercise to test my understanding.” The model will likely explain and then produce an exercise.

A very interesting pattern in education is Socratic prompting – the model asks the student questions instead of just giving answers, to lead them to the answer. You can prompt a model to do that: “When I ask you a math homework question, do not give me the answer directly. Instead, ask me guiding questions to help me figure it out, one step at a time.” Now the student asks, “How do I solve x + 5 = 12?” The model should respond with something like “What do you think the first step is? Perhaps subtracting 5 from both sides?” etc. This is quite an advanced prompting technique to enforce an interactive teaching style.